“I had no feelings in carrying out these things because I had received an order to kill the eighty inmates in the way I had already told you.

That, by the way, was the way I was trained.“

– S. S. Captain Josef Kramer, about the gassing of eighty Jews at Auschwitz; as quoted in “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich” by William L. Shirer

A Muslim teenager was lynched on a train India on 23rd June. Apparently, a group of people attacked four Muslims, accusing them of being beef eaters, and mercilessly beat them up. Later on, sixteen-year-old Junaid died of his injuries. News reports say that the amount of blood in the train shows the enormity of the gruesome violence.

While I was distressed by the news (my son sixteen, dammit!), I must sadly say that I was not surprised or shocked. Gratuitous violence towards Muslims has become the new normal in India. One glances at the headlines, registers the fact, and moves ahead – and another death becomes a statistic (except for the family of the person murdered, that is).

Why is it so? How can people accept (if not condone) such atrocities as part of the daily grind?

Maybe, the answer can be found in Hitler’s short-lived Third Reich – its ‘philosophy’ and application.

Over a period of six months from December 2016 to May 2017, I read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William L. Shirer’s definitive account of the Third Reich under the evil and mad genius, the warlord Hitler. Hitler expected that the Reich will last for a thousand years – in reality, it lasted just over 12 years. In those twelve, the Fuehrer managed to create hell on earth for the people whom he ruled over as well as in those areas which he conquered; the war he initiated managed to destroy 50 to 80 million people all over the world.

Nowadays we wonder – how did such a lunatic from the fringe enter mainstream politics, and even without any sort of a proper majority, manage to take over the country and win the support of the majority of the German populace for his unspeakably evil schemes? Do we have to accept there is some basic flaw in the German character that makes them susceptible to this sort of brainwashing? Or is it historic, something to do with the virulent anti-Semitism of the West? Was it a unique phenomenon which, after having happened once in history, will never happen again?

To the first two questions, I would agree partially: to the last, however, I would have to say no to the last. It can happen again, and in fact, is happening all over the world.

Humanity in general, and not only Germans, is always susceptible to projection. A race proud of its antecedents, lately fallen on bad times in their own estimation, looks for a scapegoat to apportion blame. In Weimar Germany, the victim the inheritors of the mythical Aryan race found was, not unsurprisingly, the Jew: the killers of Christ, the legendary hawkish money-lender, Fagin who inducts young children into a life of crime…

If we study how anti-Semitism developed side-by-side along with the legend of the Aryan race who colonised and “civilised” the known world, we will definitely find the race superiority complex of the European masquerading as “philosophy” and “history”. The Jew has been cast in the role of the villain who apparently spoilt the purity of the European race, descendants of the Aryans who had a pristinely pure monotheistic religion. This theory, which gained traction during enlightenment, was further developed into the concept of the ubermensch by Nietzsche and later developed into Nazism (as explained by Dorothy M. Figueira in her fascinating book Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority Through Myths of Identity).

India, taking nourishment from the same mythical root, found a different enemy to blame for their fall from grace – the Muslim. The myth of the Middle Eastern marauder, running amok over the temples and ashrams of India, killing Hindu priests and kidnapping and raping Hindu girls slowly became an accepted fact in the Hindu cultural milieu, half-truth though it was; the British who wanted to divide the country along religious lines also promoted this myth so that a permanent fault line (which created the partition in 1947) was created. This fault line has been growing wider ever since, and now we are seeing a country on the verge of fracture.

As the resentment grows, so does the intolerance – and the indifference to violence against the minorities. It does not happen on one fine day (as they are fond of saying, it did not start with the gas chambers). It requires years of patient propaganda, the feeding of the latent hatred by a dedicated ideological group.

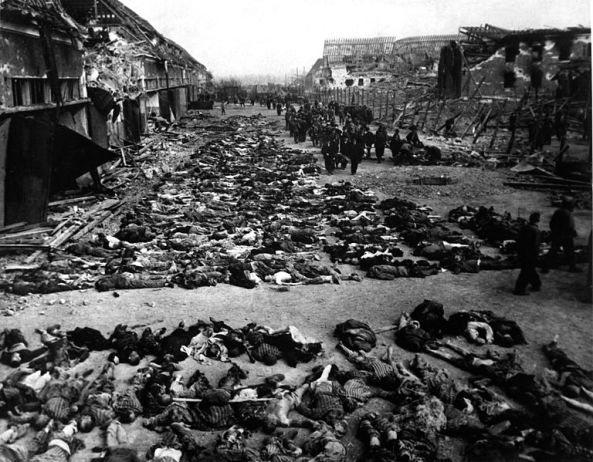

Attribution: Bundesarchiv, Bild 119-2406-01 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Shirer writes:

No one who has not lived for years in a totalitarian land can possibly conceive how difficult it is to escape the dread consequences of a regime’s calculated and incessant propaganda. Often in a German home or office or sometimes in a casual conversation with a stranger in a restaurant, a beer hall, a cafe, I would meet with the most outlandish assertions from seemingly educated and intelligent persons. It was obvious that they were parroting some piece of nonsense they had heard on the radio or read in the newspapers. Sometimes one was tempted to say as much, but on such occasions one was met with such a stare of incredulity, such a shock of silence, as if one had blasphemed the Almighty, that one realized how useless it was even to try to make contact with a mind which had become warped and for whom the facts of life had become what Hitler and Goebbels, with their cynical disregard for truth, said they were.

(Shirer is writing here about Nazi Germany – but as far as I can see in democratic India in the 21st Century, the same applies for any right-winger: and I suspect that it may be applicable globally. They have come to a stage where they cannot differentiate between fact and fantasy. They live in a fantasy world created in their minds, where facts are what they want them to be. So in a way, Kellyanne Conway is right; there are “alternative facts”, even though us ordinary mortals cannot see them.)

Thus, we move towards the practice of evil as a daily affair – an incredibly banal one, as Hannah Arendt would say. Hence the quote at the beginning of this post – just a soldier doing his job.

I believe – in fact, I am terrified – that India has progressed on this path to fascism at a frightening speed in the past three years. Modi and the BJP government are certainly to blame, but they are only the symptoms. The cancer goes much deeper. Sadly, we see the same happening in many democracies – USA, Turkey etc. Unless we identify the root of the evil in our own mind and cast it out, we may end up with another Hitlerian era, which will be much more dangerous in the current world.

In our new age of terrifying, lethal gadgets, which supplanted so swiftly the old one, the first great aggressive war, if it should come, will be launched by suicidal little madmen pressing an electronic button. Such a war will not last long and none will ever follow it. There will be no conquerors and no conquests, but only the charred bones of the dead on an uninhabited planet.

Yes, indeed.