Aurangzeb has been cast as an unmitigated villain by the British, a myth which has been enthusiastically adopted by Hindutva apologists to further their agenda of projecting Muslims as cruel bigots and ruthless killers. The truth, as usual, is much more nuanced.

Aurangzeb has been cast as an unmitigated villain by the British, a myth which has been enthusiastically adopted by Hindutva apologists to further their agenda of projecting Muslims as cruel bigots and ruthless killers. The truth, as usual, is much more nuanced.

The casual reader and scholar alike, however, should be wary of what constitutes historical evidence and a legitimate historical claim. Individuals that claim to present ‘evidence’ of Aurangzeb’s supposed barbarism couched in the suspiciously modern terms of Hindu-Muslim conflict often trade in falsehoods, including fabricated documents and blatantly wrong translations. Many who condemn Aurangzeb have no training in the discipline of history and lack even basic skills in reading premodern Persian. Be sceptical of communal visions that flood the popular sphere. This biography aims to deepen our remarkably thin knowledge about the historical man and king, Aurangzeb Alamgir.

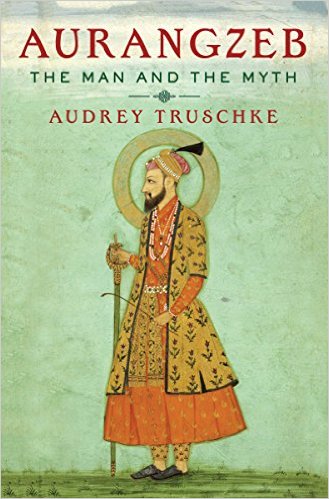

Thus concludes Audrey Truschke the book Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth, and we would do well to heed her words. So much of what we have been taught as history have been infected by politics: originally by the designs of our colonial masters, then by the political outlook of the “brown sahibs” who took over our country from them, and lastly by the strident (if illogical) claims of our aggressive Hindu right. Unfortunately, all three found it expedient to demonise Aurangzeb – the British to create the myth of centuries-long Hindu-Muslim conflict, the Congress to prove their historical role in solving that conflict and the BJP to to sustain the myth of the marauding Muslim and the tolerant and long-suffering Hindu. This is the myth that most of us grew up with, and this is the myth which still proves remarkably resilient.

No person is uni-dimensional (other than comic book heroes and villains). This is why narratives which run counter to the popular one are important; why articles describing Gandhi’s racism and Mother Theresa’s religious fundamentalism need to be read (though not necessarily agreed with). Only when we try to look at historical personages in all their complexity shall we be able to see the past in all its multi-hued glory – which in turn, will illuminate the present.

Audrey Truschke has produced a very readable book (though rather short on substance) on the Emperor which does a laudable job of debunking the myth. Though one expects a more detailed analysis, this book should serve as a starting point for any interested reader on the controversial sovereign.

The charges levied against Aurangzeb are mainly two: (1) he was a bloodthirsty monster who treated his enemies savagely and murdered his kin to gain the throne and (2) he was a religious bigot who relentlessly persecuted Hindus and destroyed temples. The author shows that both of these charges are rooted in half-truths which are more dangerous than lies, because they can so easily fool the gullible.

The charges levied against Aurangzeb are mainly two: (1) he was a bloodthirsty monster who treated his enemies savagely and murdered his kin to gain the throne and (2) he was a religious bigot who relentlessly persecuted Hindus and destroyed temples. The author shows that both of these charges are rooted in half-truths which are more dangerous than lies, because they can so easily fool the gullible.

As to the first charge: yes, Aurangzeb did that – but it was no more than any other Mughal prince would do. Wars of succession for a vacant throne was the norm in the dynasty. There was no primogeniture – the popular saying was ya takht ya tabut (either the throne or the grave). Although Dara Shukoh, Shah Jahan’s eldest and favourite son has been treated very kindly by history, in the matter of squabbling for the throne, he was as good (or as bad) as the other three; Shah Shuja, Aurangzeb and Murad. All four wanted the kingship and were willing to do away with their brothers. Aurangzeb was the one who won out.

There have been many recorded instances of Aurangzeb treating his enemies cruelly (Shivaji’s son Sambaji is the example which immediately comes to mind) – but then, there are other instances when he proved lenient. Again, there is no evidence to prove that he was more savage than any average medieval king.

Now the biggest charge – that of the religious bigot who systematically tried to wipe out Hinduism – has to be examined. Ms. Truschke provides convincing evidence to illustrate that he was no bigot: only a strict and pious ruler, obsessed with an idea of justice. Obviously he would have considered Islam the true religion and all others as false, but it is clear that politics trumped faith on most occasions. The author quotes Richard Eaton, the leading authority on the subject, to establish that the number of confirmed temple destructions is just over a dozen . And many of those acts had political roots. (We must bear in mind that even Hindu kings sacked and pillaged the temples in rival’s domain – the Shaiva/ Vaishnava conflicts are obvious examples.)

There are also ample examples of the emperor continuing the Mughal system of patronage of Hindu and Jain communities. Also, Aurangzeb had a number of Hindu officials under him, some of whom enjoyed very high ranks. Hardly to be expected of a fanatic Hindu-hater! However, it is clear that he was no Akbar, as he reimposed the Jizya (tax on non-Muslims) even though it is very doubtful whether the order was implemented in practice.

There are also ample examples of the emperor continuing the Mughal system of patronage of Hindu and Jain communities. Also, Aurangzeb had a number of Hindu officials under him, some of whom enjoyed very high ranks. Hardly to be expected of a fanatic Hindu-hater! However, it is clear that he was no Akbar, as he reimposed the Jizya (tax on non-Muslims) even though it is very doubtful whether the order was implemented in practice.

(Here I must say that I do not accept what the author says without a pinch of salt. I have read other believable sources, notably the Malayalam author Anand, who claim that Aurangzeb was more fanatical than most. Instead of swinging to one or other end of the pendulum, we must weigh the evidence and decide for ourselves.)

Ultimately, Aurangzeb was a strong king who ruled for more than five decades and who expanded the Mughal kingdom across a major part of the subcontinent. Instead of a cartoon villain, he was a complex character who was composed in parts of the good, the bad and the indifferent, much like all of us.

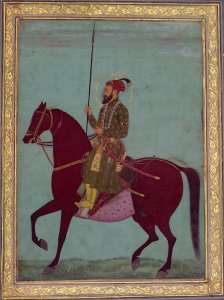

Aurangzeb nonetheless defies easy summarization. He was a man of studied contrasts and perplexing features. Aurangzeb was preoccupied with order – even fretting over the safety of the roads – but found no alternative to imprisoning his father, an action decried across much of Asia. He did not hesitate to slaughter family members, or rip apart enemies, literally, as was the case with Sambhaji. He also sewed prayer caps by hand and professed a desire to lead a pious life. he was angered by bad administrators, rotten mangoes, and unworthy sons. He was a connoisseur of music and even fell in love with the musician Hirabai, but, beginning in midlife, deprived himself of the pleasure of the musical arts. Nonetheless, he passed his later years in the company of another musician, Udaipuri. He built the largest mosque in the world but chose to be buried in an unmarked grave. He died having expanded the Mughal kingdom to its greatest extent in history and yet feared utter failure.

A complex character indeed – and one worthy of more attention than that which has been given.